Note: To view the discography tables on a smaller device like a smartphone or tablet, please flip the device to the side.

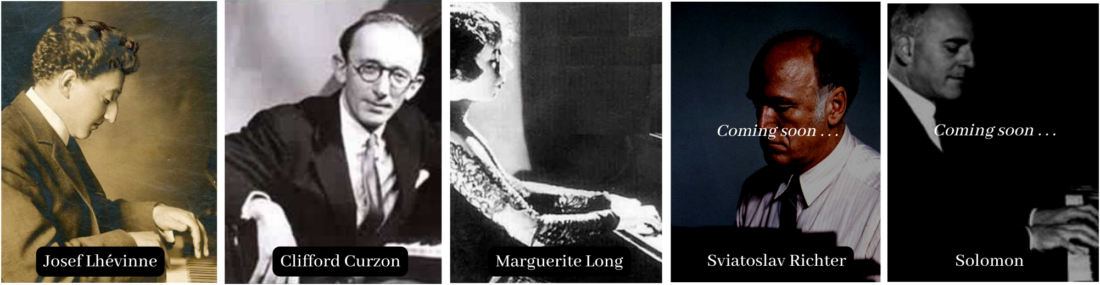

Each pianist’s full list of recordings1I will make every attempt to track down all recordings of the artist that have been released on CD or digitally, including some that have not to the extent that they are obtainable. However, for bigger-name artists with large numbers of private, live, or alternate performances (e.g., Vladimir Horowitz or Sviatoslav Richter), certain more obscure or difficult-to-obtain recordings may deliberately be excluded. For the most part, amateur or audience recordings will not be taken into account unless they either have been released on a professional label or are especially noteworthy (e.g, the particular work does not appear elsewhere in the pianist’s discography). By all means, please contact me if you believe that an important recording is missing. is available in tabular format under the “Pianist Discographies” heading on the main menu, In addition to containing factual details about each recording, the discography tables include a final column containing my at-a-glance subjective rating of the performance on a five-star scale, explained in a key above the table. A few notes on the table heading categories:

- Composer and work (headings 1 & 2)—Entries are listed alphabetically, proceeding according to composer’s last name, then work title, then opus or other number. In cases of multiple performances of the same work, the order is from earliest to latest in terms of recording date. The “work” entry includes a link to the performance on YouTube2As a general disclaimer, although I have included these YouTube links as a resource, I am in no way advocating the download of the audio-file versions to one’s personal computer systems since such activity may technically be in violation of copyright law. Granted, few of the albums or tracks at issue here—especially those from third-party labels outside the big guns like Decca, DG, or Sony Classical—are likely to have ardent copyright defenders (or renewers) owing to their limited long-standing success in the mainstream commercial marketplace. Note, too, that even historical recordings made for bigger labels are often provided to YouTube for free streaming purposes, and some (those made more than around 95 years ago) may be in the public domain anyway. if it is available.3Note that the performances on YouTube tend to be in the lower-quality mp3 format as do many of those on online music retailers with a wide classical selection such as Amazon or Classical Archives. Those who desire a lossless format should consider purchasing digital tracks or albums from a vendor such as Apple Music or Presto Music that offers it. On the other hand, those who crave a full hard-copy “album” experience replete with liner notes, as well as full CD-quality sound, might have better luck these days on a trading site like eBay or Discogs. For multipart works, links are to each individual movement or piece or to the entire work depending on the version located on YouTube. As a space-saving measure, major and minor keys are represented by capital and lowercase letters (i.e., without the actual words “major” or “minor”), respectively, as is a common convention in music typography.

- Other performers (heading 3)—For collaborations, a listing of the other participants in the performance (e.g., instrumentalists, conductor & orchestra).

- Source CD label (heading 4)—A listing of the label that released the particular recording on compact disc. By “source,” I mean that I listened to the version of the recording put out on this particular label, whether from my own private collection, audio streaming, or YouTube. For re-releases of previously published material, of which there are many in the classical piano world, I include the new label first followed by the original label in parentheses.4Unlike most discographies, these do not include every release (and re-release) of the same material for recordings that have been issued multiple times. For practical listening purposes, I find that approach overwhelming and confusing, especially since quite a few individual releases of historical piano recordings are out of print or their labels defunct. Instead, I have chosen the release I believe to be the most “definitive”—that is, the one on the original or third-party label that is the most widely known or available either for streaming or on hard copy. Recordings that were never released on any CD label (only on LP, for example) are marked with an italic Unreleased, with the original label indicated in parentheses if applicable.

- Source CD title (heading 5)—Titles are generally cited exactly as they are on the album cover, with minor adjustments such as the addition of em dashes or colons to reflect subheadings. Also included for the entries in this column is a link to the page on Amazon where a digital or physical copy of the track or related album can be purchased (or another vendor if not available on Amazon).

- Recording date and place (heading 6)—When and where the pianist made the original recording, including the specific date, geographical location, and venue. If the location of a particular venue seems obvious, I omit it (e.g., Carnegie Hall, the Moscow Conservatory). Note that I tried to obtain as complete a listing as I could for each of these, but a few remain incomplete according to the sources I checked, which include liner notes, other discographies, and biographies.

- Rating (heading 7)—As noted above, my subjective rating of how a particular performance stacks up in the annals of piano recording. In addition to the sui generis aesthetic merits, factors taken into account in this rating include the work’s ubiquitousness on recording and, if applicable, how it compares with the pianist’s other renditions of the same work. Naturally, the ratings for much-traversed segments of the piano literature with scads of interpretations (e.g., the Chopin etudes, the Beethoven sonatas, the Debussy preludes) tend to be more critical than those for piano-aficionado esoterica (e.g., the Dohnányi etudes, the Hummel sonatas, the Miaskovsky piano sonata). For multipart works, I also may occasionally provide a separate rating for a particular movement or piece in the set that I think is of considerably higher or lower quality than the others.

Have a correction or clarification? Please let me know.